< Back to Patient safety & hygiene practice

Authors

Schwindt E, Hogeveen M, Härting H, Jessie M, Pateisky N, Schwindt J

Infants, parents, healthcare professionals, neonatal units, and hospitals

Healthcare professionals, neonatal and paediatric units, and health services

Incident reporting systems must be mandatory for all neonatal wards and have to be embedded in comprehensive safety programmes to effectively improve healthcare safety.

To improve patient safety, it is fundamental to learn from critical incidents. (1–7) High-risk high-consequence systems, such as the nuclear industry and, more broadly recognised, the aviation industry, are commonly known to implement Critical Incident Reporting Systems (CIRS) to reduce the risk of potentially catastrophic events. (3,8,9) Hospitals are high-risk high-consequence environments as well, which makes CIRS an attractive tool to enhance patient safety. Fortunately, an increased use of CIRS in the health sector can be observed, facilitated also by several nationwide policies. (10,11) However, in healthcare systems, concerns about the effectiveness of CIRS were raised mainly owing to the isolated implementation of CIRS and a persistent lack of numerous other safety measures. (1,2,12) A standalone error reporting system without other components may not be perceived as the helpful tool it may well be. (13,14) Therefore, multiple studies are available analysing comprehensive safety bundles, which include, beneath others, the implementation of error management systems. (15) These safety bundles include the implementation of standards, checklists, compulsory regular training, deliberate employee selection, and the development of a safety culture based on just culture principles. (4,16) Also, available CIRS systems often lack basic requirements for effective incident analysis, which might lead to ineffective detection, prevention of preventable harm leading to a false impression of safety. (1,2,12)

The barriers to incident reporting are well known, also in hospital settings. (1,10,12,17) For successful work on patient safety with long-lasting effects, it is paramount to resolve these issues.

For parents and family

B (Moderate quality)

Audit report1, patient information sheet2

A (Moderate quality)

Audit report1, parent feedback, patient information sheet2

For healthcare professionals

A (Moderate quality)

Minutes of team meetings

A (High quality)

Training documentation

A (Moderate quality)

Audit report1, healthcare professional feedback

A (Moderate quality)

Healthcare professional feedback, training documentation

A (High quality)

Healthcare professional feedback

A (High quality)

Healthcare professional feedback

A (High quality)

Healthcare professional feedback

For neonatal unit

B (High quality)

Healthcare professional feedback, minutes of team meetings, training documentation

B (High quality)

Healthcare professional feedback

B (High quality)

Healthcare professional feedback

A (High quality)

Healthcare professional feedback

For hospital

A (High quality)

Audit report1

A (Moderate quality)

Audit report1

B (High quality)

Healthcare professional feedback

B (Moderate quality)

Audit report1

A (Moderate quality)

Audit report1

For health service

B (High quality)

Training documentation

B (High quality)

Healthcare professional feedback, training documentation

1The indicator ‘audit report’ can also be defined as a benchmarking report.

2The indicator ‘patient information sheet’ is an example for written, detailed information, in which digital solutions are included, such as web-based systems, apps, brochures, information leaflets, and booklets.

For parents and family

B (Moderate quality)

For healthcare professionals

N/A

For neonatal unit

N/A

For hospital

B (Moderate quality)

B (Moderate quality)

B (Moderate quality)

For health service

B (Moderate quality)

B (Moderate quality)

B (Moderate quality)

For parents and family

For healthcare professionals

For neonatal unit

For hospital

For health service

After numerous catastrophic events in the last century, the aviation industry was forced to improve flight safety. In a decade-long process of systematic investigations of accidents and incidents, a bundle of measures was implemented step by step. These measures included deliberate employee selection, standardisation of processes, the obligatory use of checklists, mandatory training and regular checking and – above all – the development and support of a safety culture based on just culture principles. As the last step in this process critical incident reporting systems (CIRS) were implemented in order to continuously improve and to identify new issues to increase aviation safety. (3,8) Similar measures were undertaken in other risk areas, e.g. the nuclear industry. (9)

Healthcare shares the high-risk, high-consequence characteristics of the aforementioned industries. Yet, CIRS has only recently begun to attract the medical field, commencing its integration to hospitals after the widely recognised publication “To err is human”. (7) To date, an increasing number of medical institutions, partly pushed by nationwide incentives (10,11), adapted CIRS to report errors and to improve the care and safety of patients.

It must be emphasised, however, that the implementation of CIRS in other high-risk areas was implemented as a last step, only after a whole bundle of safety measures had been established. In many medical institutions, however, CIRS is operated as the first or often isolated measure to increase patient safety. (1,16) CIRS on its own, without the existence of the underlying basis for it (how to report, how to respond, etc.) is not sufficient (13,14,49) and thus inadequate to contribute to a successful improvement of patient safety in the long run. (1,2,12)

Requirements for a functioning CIRS

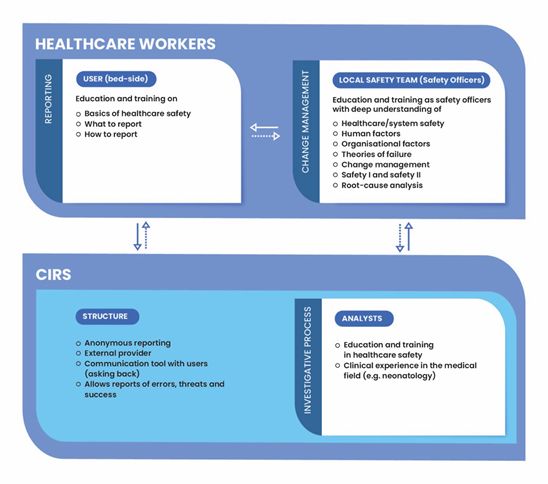

In general, for the effective processing of reports, several requirements need to be met that are listed in the components of the standard and are described here and in figure 1 in more detail:

Since healthcare safety so far is still underrepresented in most educational curricula, medical employees only rarely have education or training in healthcare safety; often there is a lack of knowledge on how to identify safety issues or to implement changes. It has been shown that a lack of information of the healthcare workers on what and how to report seems to be an important barrier that hinders employees from reporting incidents. (1,10,12,35,39,50) Regular training on what and how to report, therefore, seems to be the fundamental basis of a functioning CIRS. While the exact interval for recurrent training is unclear, training effects likely deteriorate after 12 months of the intervention. (44) Recurrent training intervals of 6-12 months, similar to the aviation industry, therefore, are advisable.

What to report:

Regarding the results of most reporting systems in the medical field, the focus still seems to be on the number of reports (“the more the better”). (1,22,35) However, it is the investigative process that should be the core measure of CIRS as well as the strategies to implement the required changes. (1,34,38,46) Therefore, it is not effective to report every single incident or threat. (1,35) Instead, employees need to be informed (through education and training) on how to deliberately decide, which incident implies the potential to learn/to improve safety, and which incident does not. (1,22,35) Furthermore, all employees need to understand which adverse events are mandatory to report (see below).

How to report:

Employees require education and training on how to describe an incident and what language to use. (51) This facilitates the reporting and also the investigative process can be done as easy and as effectively as possible.

Voluntary or mandatory?

Unlike in aviation, reporting in medicine happens on a voluntary basis. Voluntary (and anonymous) reporting is reasonable when it comes to delicate issues preferably handled confidentially and which might not be reported otherwise. However, it cannot be accepted that the decision, whether to report an incident with preventable patient harm, relies on the willingness of certain individuals which commonly results in underreporting of critical issues. (1,19,20,39) Therefore, trigger tools should be used (43), i.e. adverse events with an obligation to report have to be clearly defined and brought to the knowledge of all employees. (1,22,35,43) The purpose of the compulsory part of the reporting system is to monitor the frequency of events and to track undesired outcomes. (22) The basic prerequisite is that notifiable events are being reported in practice. A decrease in reporting can mean both an improvement in this area, as well as a lack of safety culture and compliance. (13,14,49) However, a functioning mandatory reporting and visualisation of adverse events might be helpful in creating the pressure on decision-makers to provide sufficient resources for healthcare safety issues.

Hence, an effective reporting system on the one hand enables voluntary reports of threats, errors and success, and on the other hand includes the mandatory report of clearly defined adverse events.

Since the investigative process is the core of every reporting system, analysts require not only knowledge in the certain medical field (e.g. neonatology) but also need appropriate knowledge, skills and attitude, basic education and recurrent training and deep understanding of healthcare safety. (22) This includes, amongst others, knowledge about safety and just culture, human factors, organisational factors, principles of safety I and safety II, root-cause analyses and change management.

The following qualities are essential for a well-designed reporting system in order to enable effective reporting and processing (1,17,22,39):

It is important to emphasise that healthcare safety is a very extensive and complex field and a local safety team with education and regular training in healthcare safety is paramount for success of CIRS. A randomly chosen person for safety issues without specific knowledge (sometimes involuntarily nominated by superiors, working alone and without appropriate resources) will not be able to effectively resolve safety issues.

The local safety team serves as a link between CIRS-analysts and users (healthcare workers) when it comes to the implementation of proposed solutions and adaptation on certain local conditions. CIRS-analysts provide the information of the reported incidents, results of the root-cause analysis (or complete them together with the local team) and – if possible – provide solutions for the reported safety issue. The local safety team then discusses the proposed solutions on feasibility considering the certain conditions of the ward and induces possible ways on how to implement the necessary changes.

The process of reporting, investigation and change has to be continuously monitored and evaluated. Evaluation can be done best by the users themselves, working bed-side and, therefore, experiencing impact of changes first-hand. However, sufficient (financial and personal) resources for monitoring must be provided and reports must be demanded on regular intervals by the management.

Financial aspects of CIRS:

Establishing and maintaining a successful and effective CIRS with all of the above-mentioned components (CIRS system, personnel, education and training, etc.) requires major financial resources. Such high initial costs combined with non-existing legal obligations appear to be a deterrent and may be the reason why CIRS is often not fully implemented. However, sustainable planning is required and a comprehensive CIRS system can be seen as a financial investment in risk-reduction. (52) It is estimated that on average one adverse event in an acute patient exceeds 13,900 € within one year and, therefore, is doubling the normal healthcare expenses per patient; the estimated accumulated costs of adverse events per annum in Danish Hospitals alone is 3.1 billion €. (51) Also, approximately 15% of the total hospital expenditures in OECD countries can be attributed to adverse incidents, approximately half of which is considered avoidable patient harm. (31) Furthermore, the calculated costs thereof are immense: 606 billion dollars, equalling 1% of the economic output of all OECD members combined, are spent on avoidable safety lapses. (31) Quality improvement strategies such as the implementation of a comprehensive and functioning incident reporting system, therefore, seem to far outweigh the costs of implementation and maintenance.

CIRS is not a measuring tool

It is important to notice that CIRS is neither effective for benchmarking, measuring patient safety, nor for analysing improvements over time. (12,22) Some reports might reflect on low occurrence of errors, but as discussed above it might as well point to a low willingness to report, insufficient safety culture and non-reporting. (13,14,49) Therefore, to reiterate, the core of CIRS must not be reporting but the focus must be on effective, long-lasting solutions to improve healthcare safety.

Cultural aspects and just culture

In order to establish a functional and meaningful incident report system, certain interwoven culture-related aspects have to be taken into account. A common safety culture must be developed (4,39,45,53), in which failure/error or adverse events do not lead to shame or blame of the reporting healthcare professionals. Instead, employees must feel psychologically safe to report without fear. Thus, the first question after an event must not be “Who did this” but “How could this happen?”. Errors, for example, that occur due to system-immanent conditions must not be at the expense of individual employees.

Following just culture principles, an analysis must classify for each failure whether it was caused by human error (unintended outcome, often system-immanent, could have happened to anyone), due to risky behaviour (risky, but deliberate decision, made e.g. under pressure), recklessness (knowing that the action is not safe) or on purpose. (45,53,54) Depending on each individual case, failure that occurred because of intentional non-compliance, due to recklessness or risky behaviour must not be tolerated and employees must be aware of both the differences and the consequences of these actions.

Recommended literature

September 2022 / 1st edition / next revision: 2025

Recommended citation

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Facebook. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationYou are currently viewing a placeholder content from Instagram. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationYou are currently viewing a placeholder content from X. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More Information