< Back to Patient safety & hygiene practice

Authors

van der Starre C, Helder O, Tissières P, Thiele N, Ares S

Infants, parents, and families

Healthcare professionals, neonatal units, hospitals, and health services

Patient safety and quality improvement activities are fully integrated in clinical practice.

Infants admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) are at a high risk of being harmed by lapses in quality or safety. Improving patient safety is an important component of high quality care and requires the support of an appropriate system for the identification, investigation and development of learning from quality issues. Although there are several schemes for quality improvement, local leadership and implementation are critical to improving outcomes for ill infants. (1–6)

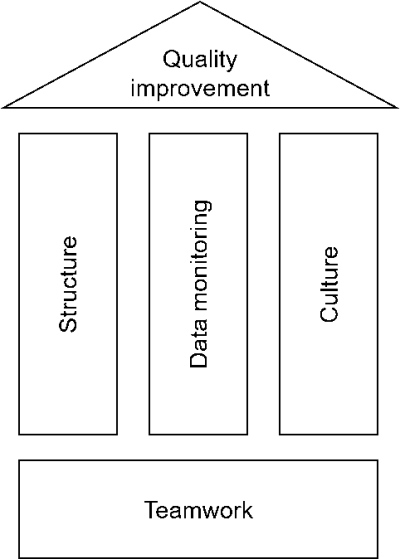

There are six potential domains in quality of healthcare: patient centeredness, patient safety, efficacy, efficiency, timeliness, and equitability (5), which should form the basis of any quality programme in neonatal care. These may be addressed using three major components: structure, data monitoring and culture. (7)

A Quality system needs to be championed at hospital board level but is led from within the neonatal team, supported by the quality improvement staff. Structural components also include a system capturing data to monitor key indicators as prioritised by the neonatal team. The system should develop a safety culture in which transparency, blame free reporting and the development of learning from clinical events reported within the system. Units should establish an advisory board to coordinate and direct quality improvement initiatives.

For parents and family

B (Moderate quality)

Patient information sheet1

B (Moderate quality)

Parent feedback

B (Moderate quality)

Training documentation

B (Moderate quality)

Parent feedback

B (Moderate quality)

Guideline

For healthcare professionals

B (Moderate quality)

Guideline

B (Moderate quality)

Training documentation

B (Moderate quality)

Audit report2, guideline, training documentation

B (Moderate quality)

Audit report2, clinical records

B (Moderate quality)

Staff feedback

For neonatal unit

B (Moderate quality)

Guideline

B (Moderate quality)

Audit report2, guideline

B (Moderate quality)

Audit report2, guideline

B (Moderate quality)

Audit report2, guideline

B (Moderate quality)

Audit report2, training documentation

For hospital

B (Moderate quality)

Training documentation

B (Moderate quality)

Guideline, audit report2

B (Moderate quality)

Guideline, audit report2

B (Moderate quality)

Audit report2

B (Moderate quality)

Audit report2

For health service

B (Moderate quality)

Guideline

B (Moderate quality)

Audit reports2

1The indicator “patient information sheet” is an example for written, detailed information, in which digital solutions are included, such as web-based systems, apps, brochures, information leaflets, and booklets.

2The indicator “audit report” can also be defined as a benchmarking report.

For parents and family

N/A

For healthcare professionals

N/A

For neonatal unit

N/A

For hospital

N/A

For health service

B (Moderate quality)

For parents and family

For healthcare professionals

For neonatal unit

For hospital

For health service

It may seem quite logical and even to be expected that a lot of attention has been given to improvement of quality of care in neonatal care. The extremely vulnerable and seriously ill patients in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) are at a high risk of being harmed by lapses in quality or safety. Nevertheless, improving healthcare quality has proven to be a challenging undertaking, that foremost requires long term dedication. It has become clear that the science of improvement, human factors and implementation are indispensable in increasing quality and patient safety. This standard of care attempts to highlight the most relevant topics and tools that NICUs can apply in their quality management.

The Institute of Medicine has defined six domains in quality of healthcare: patient centeredness, patient safety, efficacy, efficiency, timeliness, and equitability. Quality and safety management should encompass all these topics. Obviously that poses a very daunting task for NICUs, which nonetheless needs to be addressed. The first thing that needs to be clarified, is that no single quality management system will fit all NICUs; customisation is in order, as each NICU may need to have to address different priorities in quality and patient safety. Also, the instrument that works well in one NICU will likely be less or not successful in another NICU; for instance, the applicability of a programme to increase flow of patients and reduce length of stay would be very variable among different settings.

Patient centeredness has been viewed as an evident requirement for neonatal care and the “family unit” as the “patient” is a widespread point of view. The implementation of rooming in facilities for mothers, mother and child suites, and shared care programmes are some of the most apparent developments. The increasing use of individualised neonatal care programmes is another example of application of patient-centred care that directly benefits both patients and parents. The challenges for the future in infant- and family-centred care lie in creating shared decision-making. Together with parents, we will need to examine what is needed for all stakeholders, such as parents, healthcare workers, hospitals etc., to implement and maintain shared decision-making. By involving parents in the care for their children, not only can we improve that care, but also advance knowledge and experience of quality and safety in a broader way.

Since the publication of the landmark report “To err is human” (5), the quality and patient safety movement, which had taken off with a slow start, has gained more and more momentum. Numerous initiatives and organisations dedicated to quality improvement have been created, such as the Institute for Healthcare Improvement in the USA and the Health Foundation in the UK. Research in the fields of quality, patient safety, implementation, innovation and human factors, has exploded. As the research and knowledge of safety and quality has increasingly been shared, it became evident that a number of basic requirements for improvement are necessary for all healthcare settings.

First of all, a system or structure for Quality and Patient Safety Management (QPSM) needs to be in place. Roles, tasks and responsibilities have to be defined. It needs to be clear who is doing what, and who is accountable for which components of the management system. This needs to be facilitated and supported actively by boards, directors, and (middle) management; quality management will undoubtedly fail when it is simply added to the everyday tasks and activities of the engaged frontline staff. Another necessity relates to improvement skills. Frontline staff and middle management involved in quality improvement need to collaborate with co-workers schooled in change management, as healthcare professionals usually are not trained in the skills for developing and implementing new processes, procedures etc. Next to this, each NICU needs to determine what data to monitor and in what way. In order to be able to prioritise, implement, monitor, adapt and create a success of any improvement initiative, data need to be collected relevant to the problem that needs to be tackled (see Data collection & documentation).

The last pillar of the QPSM is culture. How is the safety climate in a NICU, a hospital, a country? Is there a “just culture” where openly discussing errors and mistakes is not only possible without fear for repercussions, but in fact welcomed as an opportunity to learn? In this respect, leading by example is one of the most powerful modes of improving the safety culture in any setting. Directors and heads of departments that welcome feedback on their (lack of) adhering to hand hygiene rules, will likely see an increase in commitment from frontline staff and patients/parents. Next to leadership in setting the standard for the desired work-related behaviours, they also need to facilitate teamwork and teamwork training. Teamwork is more and more recognised as the foundation of healthcare and thus it needs to be addressed. As has been proven numerous times, expert teamwork is not created by simply putting a number of experts together, but requires training, both in acute care settings such as the NICU, as well as other settings such as for instance an outpatient department. Healthcare frontline staff are well trained professionals in their field of expertise, however, the non-technical skills that are required for teamwork quite often have not received the attention they require. Communication, stress management, leadership, decision-making, risk management, developing a shared understanding of the situation are topics of training, education, and discussion that can and should be addressed. Especially interdisciplinary training is an upcoming phenomenon in healthcare, that addresses these non-technical skills. Teamwork and culture also relate to the notion that patients and family should be welcomed as members of the team. Obviously, healthcare in itself means partnering up with patients, as without them, there would be no need for healthcare providers. However, integrating parents in the NICU team can be quite challenging and there may be a number of barriers. For instance, the events surrounding the birth of a preterm child can be extremely stressing for parents, thus decreasing their ability in shared decision-making. Or the frontline staff feel they cannot properly discuss the decisions during the rounds if the parents are present. These potential issues obviously need to be explored and dealt with before teaming up with the parents can reach its full potential. A large number of initiatives have been launched worldwide, so what remains is learning from each other, and from the parents/families, in how to best achieve safe, patient centred and reliable care for the most vulnerable, the NICU patients.

November 2018 / 1st edition / next revision: 2023

Recommended citation

EFCNI, van der Starre C, Helder O et al., European Standards of Care for Newborn Health: Patient safety and quality awareness in neonatal intensive care. 2018.